Books

Uncovering Tales of Japanese Internment for A PLACE TO BELONG

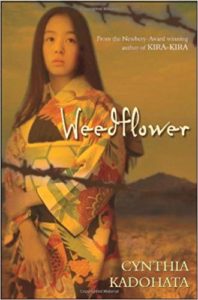

This can be a visitor put up from Cynthia Kadohata. Cynthia is the writer of Kira-Kira, winner of the Newbery Medal; Weedflower, winner of the Pen USA Award; Cracker, winner of 5 state awards as voted on by children; The Factor About Luck, winner of the Nationwide E book Award; Checked, winner of the Southern California Unbiased Booksellers Affiliation Award; and A Place to Belong. She lives in Southern California.

I believe all issues in life begin for me with my dad and mom. Once I was a younger youngster, we lived in Georgia and Arkansas cities the place there have been only a few Nikkei—folks of Japanese ancestry. All of them had been at all times concerned with the laborious work of sexing chickens—separating male from feminine chickens shortly after they hatch. My mom was a stay-at-home mother. We had been a part of a small, self-contained neighborhood, the place my household was my all the pieces. I cherished this protected, insulated existence. I cherished chasing butterflies with my siblings, I cherished going to the library with my mother, and I even cherished burning rubbish in our incinerator on Friday nights. I cherished doing nothing.

It was very totally different from the way in which my mother and pop grew up. My mother grew up in Hawaii, with seventeen folks residing in three small rooms. My dad started work at 9, choosing celery at his dad and mom’ tenant farm. Work was his life from then till he retired in his 70s. He and his second spouse lived very modestly, however he ended up having to work extra-long as a result of he was swindled out of their life financial savings. He was in truth a really naive, believing particular person. My dad and mom had been good folks, who did all the pieces they did for no different motive than to empower their youngsters in constructing higher lives.

Quickly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, 110,000 harmless Nikkei had been compelled from their houses and despatched to swiftly constructed camps in distant areas across the nation. My father and his household had been incarcerated on the Poston Relocation Heart within the Arizona desert. I wrote about this place in Weedflower. He was drafted out of that camp and served as an interpreter in Japan.

However I knew there was one other story of the camps, of the boys who refused to be drafted, of the women and men who objected—oftentimes strenuously—to their remedy. After Weedflower got here out, I felt inside myself a craving to know extra about these others. They too had labored since they had been very younger. They too had been involved in regards to the future empowerment of their youngsters.

Some folks refused to speak with me about all this after first agreeing to. Others talked, however I may inform they hated pulling up the numerous unhealthy recollections from the corners of their brains the place that they had pushed them. I believe a few of them requested themselves, Why—why does she wish to know these items? I attempted to bear in mind what I had realized in school, to simply cease speaking typically, to let the silence stretch out, till the folks you’re interviewing start to all of the sudden wish to speak. I believe the largest factor I’ve realized from writing historic novels is that nothing is about me. It’s in regards to the folks I’m interviewing, those who went via the experiences that preceded mine and allowed me to reside the life I do. Writing historic novels is a humbling expertise. Studying about the way in which during which folks fought for his or her lives and the lives of their youngsters opens up the current and imbues it with better that means.

I’d identified one aged Nikkei, Ichiro, for almost 20 years and interviewed him for A Place to Belong. He was a citizen by beginning. He got here from a household the place all of the grown-ups renounced their citizenship whereas in camp. Ichiro had been in a particular camp for resisters, protestors, leaders—males perceived as troublemakers. The renunciants in Ichiro’s household in addition to his minor siblings had been all shipped to Japan after the conflict. His father was shocked by the devastation in Japan and have become a damaged man, unable to offer for his household although he was solely in his early 50s. He turned ineffective, Ichiro stated. Ichiro took over. Earlier than the conflict, he’d been a hard-working farming son who wearing flashy garments and partied on the weekends. The women cherished him. In Japan, folks had been ravenous. His household had nothing. Ichiro took over the household at age 21, chargeable for six siblings and his dad and mom. He not solely fought to maintain them fed however fought for his or her futures as properly. Did the youthful ones wish to go to varsity someday if they might? Be part of the military? Get married and have children? He would attempt to discover a approach to make it occur. On the black market, he bought gadgets that Occupation troopers stole from the Military. It was all he knew do. He married a Japanese girl and had two children together with her. When the household acquired their citizenship again within the 1950s, all of them returned, and Ichiro began an azalea nursery. Then his spouse left him and went again to Japan—his oldest son says he used to lie in mattress listening to his father sob when she left. He didn’t suppose his father would ever cease crying. However he ultimately married once more, this time for 50 years till he died.

I’d identified one aged Nikkei, Ichiro, for almost 20 years and interviewed him for A Place to Belong. He was a citizen by beginning. He got here from a household the place all of the grown-ups renounced their citizenship whereas in camp. Ichiro had been in a particular camp for resisters, protestors, leaders—males perceived as troublemakers. The renunciants in Ichiro’s household in addition to his minor siblings had been all shipped to Japan after the conflict. His father was shocked by the devastation in Japan and have become a damaged man, unable to offer for his household although he was solely in his early 50s. He turned ineffective, Ichiro stated. Ichiro took over. Earlier than the conflict, he’d been a hard-working farming son who wearing flashy garments and partied on the weekends. The women cherished him. In Japan, folks had been ravenous. His household had nothing. Ichiro took over the household at age 21, chargeable for six siblings and his dad and mom. He not solely fought to maintain them fed however fought for his or her futures as properly. Did the youthful ones wish to go to varsity someday if they might? Be part of the military? Get married and have children? He would attempt to discover a approach to make it occur. On the black market, he bought gadgets that Occupation troopers stole from the Military. It was all he knew do. He married a Japanese girl and had two children together with her. When the household acquired their citizenship again within the 1950s, all of them returned, and Ichiro began an azalea nursery. Then his spouse left him and went again to Japan—his oldest son says he used to lie in mattress listening to his father sob when she left. He didn’t suppose his father would ever cease crying. However he ultimately married once more, this time for 50 years till he died.

I used to be there when Ichiro was dying in a mattress arrange in his kitchen. His daughter talked nonstop to him as she cleaned him with a moist towel. He was unconscious, inhaling little gasps. I do know he may hear me, she has stated many occasions since then.

As quickly as he died, his children and grandkids all requested me the identical factor: Do you’ve your notes from interviewing him? He had made their lives—in snug houses with stunning households—potential. He had left behind the women and the flamboyant garments and given himself to his brothers and sisters and fogeys. He was an American hero, and I felt like if no person wrote the renunciants story, then nobody would ever learn about all of the folks identical to him.

I knew there was a stigma hooked up to those households who took a special path into the long run, who renounced their citizenship, who had been deported. This stigma appeared fallacious to me. To me, folks with very related self-interests had been put beneath lots of strain and ended up on totally different sides, in several camps, and finally in several nations. I’m happy with all of them, either side, of their power and decency beneath excessive strain, and of the totally different, troublesome decisions they made. Each Weedflower and A Place to Belong are my love letters to all of them, and to all of us as properly, in making the troublesome decisions we face—quickly, now, at all times.